6.4 Inhibition: suppressing automatic responses

- Dylan Smith

- Dec 12, 2025

- 4 min read

Objectives:

A. Define “prepotent response.”

B. Understand that the core component of EF known as Inhibition emerges to allow

voluntary control of complex rule-bound behaviour between 3 and 4 years of age.

C. Appreciate that prepotent behaviour is a source of much challenge for children in

early educational settings.

D. Identify common classroom behaviours that reflect Inhibition and school readiness.

In the previous chapter, we learned that inhibition has many faces. Typical day-to-day functioning requires that we inhibit attention, thought, overt behavioural responses, and subcortical networks, and we use an astonishingly versatile range of processes to do so. In their seminal study on the nature of executive function, Miyake et al. (2000) focused on the behavioural domain, narrowly defining their Inhibition component as the “deliberate and controlled suppression of prepotent responses” (p. 57). A prepotent response refers to any behaviour likely to occur because it offers an immediate, familiar reward. Prepotent responses tend to be automatic and dominant and include behaviours triggered by temptation. As a result, they are difficult to derail. A hungry infant moves toward a nipple; a fearful toddler backs away from a hot surface; a sweet-toothed preschooler reaches for an unsupervised cookie.

Age-sensitive tests of executive function indicate that children can delay a response before the end of their first year (Garon et al., 2014), but the ability to voluntarily override prepotent responses in the presence of rules does not emerge until much later. In their seminal study, Zelazo et al. (1996) dramatically illustrated this developmental trajectory when they engaged groups of 3-year-olds and 4-year-olds in card-sorting games. The children were first asked to sort cards showing a blue truck or a red star into bins labelled with a red truck or a blue star. The authors found that children in both age groups can correctly sort by colour and then, when questioned, correctly point into which bin either shape should go. The converse was also true; children in both age groups can correctly sort by shape and then correctly point into which bin either colour should go. In other words, children at both ages know how to sort the cards if the sorting rule changes from colour to shape or from shape to colour. However, when given a card to sort according to the new switched rule, the 4-year-olds can do so correctly, but the 3-year-olds cannot. The overwhelming majority of 3-year-olds correctly respond to the knowledge test but persist in sorting the cards according to the first rule. They cannot yet override the prepotent correct response to the original rule.

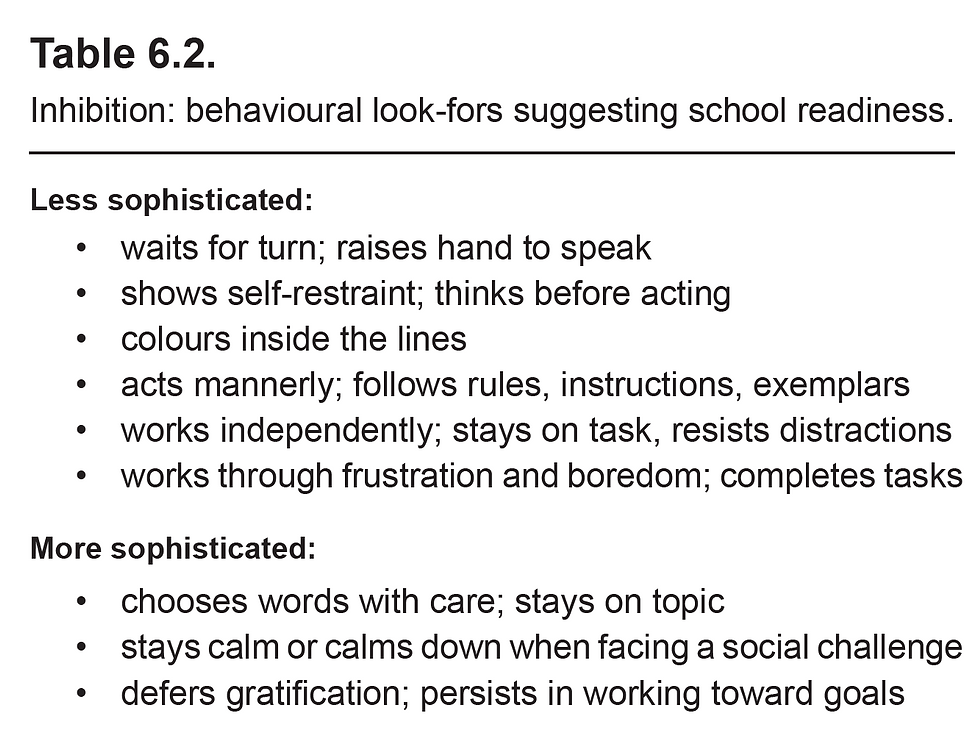

When children first leave home to enter a preschool or school setting, they experience a

constant need to be inhibiting prepotent responses. Thanks to training received at home, a

typical child’s behavioural repertoire will already include many of the more appropriate competing responses (see Table 6.2). Still, much of a young child’s typical day at school requires effortful control to counter the comfortable prepotencies they’ve learned elsewhere, and teachers are obliged to either redirect or correct them. Consider a few examples. In any early years classroom, we will likely find a child who begins the year with a habit of following their teacher around the room. Another child might persist in curling the tail of a lowercase g to the right instead of left and remain unaware of the error until the character is complete. Another child routinely leaves an assigned seat to visit the same friend whenever the class begins a new seatwork task. Yet another strikes or pushes classmates when frustrated. In the nicest way, a teacher will address prepotent missteps by encouraging the child to “make good choices,” “remember our rule,” “think before we act,” or follow the example of a friend. Strong socialization forces are at work in a classroom and include largely positive pressures from peers (modelling) and caretakers (reminders, coaching, and rehearsals). In some instances, a teacher may decide it is best to work around a prepotent behaviour with a more forgiving accommodation, for example, revising the seating plan so the wandering student may sit and work alongside his friend.

As young children graduate each year to new settings that are increasingly organized and work-oriented, there is a growing expectation to exercise inhibitory control and take responsibility for not only personal goals but also group goals. With maturation, experience, and prosocial classroom pressures, situations that once evoked a prepotent response might now cue sufficient PFC conflict to inhibit an inappropriate behaviour, affording time to deliberate on the longer-term benefit of an alternate action. Such deliberation is traditionally considered effortful, and yet some researchers have proposed that the pause is all that is needed for the strength of a prepotent response to dissipate (Simpson & Riggs, 2007; Simpson et al., 2012). Simpson et al. (2022) suggest that tasks may be designed to require a more complex response, thereby generating sufficient inhibition and reflection time for a correct response to occur.

However, other recent studies contend that imposing delays are not the most effective way to help young children deal with weak inhibitory control. For instance, Barker and Munakata (2015) found that goal-activating reminders help 3-year-olds suppress prepotent responses and that adult-imposed delays do not. They also found evidence that “spontaneous” delays originating with the child are likely to be helpful. We may interpret these findings to mean that simply giving children time to think will not guarantee how they will use that time, and that a distracting delay might successfully interrupt rash behaviour (such as counting backwards from ten when angry), but that goal reminders may be the best way to improve a child’s situational inhibitory control. In another provocative but lesser-known study, Simpson and Carroll (2018) suggested that the way caretakers frame instructions can help young children conceptualize a task in a way that reduces or even eliminates weak inhibitory control. At the time of writing and to the best of my knowledge, follow-up studies have not yet been conducted to confirm the practical benefit of that idea.

Comments